Britt discusses the 2023 flooding across the North Island and shares her thoughts on the future and the need to respond to climate change, instead of trying to prevent it.

"After the recent flooding in Tāmaki Makaurau, it can feel confusing as to what went wrong and what can be done to fix it."

For urban planners, flooding and stormwater infrastructure is one of the most important things we consider when thinking about urban development today. It hasn’t always been this way though. Today I hope to leave you with a seed for critical thought when looking at the streets around you, but also give you hope and a vision for a climate resilient future.

Something that has for far too long been side-lined as a value in the development of the cities is integrating with our natural environment. We’ve been too busy trying to build roads for our cars and houses for our people. In the process of valuing other things more than our natural environment, we covered up our streams with concrete and piped them under the ground. We built upon natural wetlands. We underestimated the importance of allowing these natural ecosystems to breathe.

Urban planning over time has reflected human values. Human values are temporal. Meaning the development of our cities have prioritised different things over time. For example, earlier centuries prioritised places of worship, such as cathedrals or mosques within central urban areas. The 20th century saw the industrial revolution, with car infrastructure forming the veins of our cities. This century, we’re dealing with rapid population growth, with urban planners trying to figure out: where do we house everyone? Do we build upwards, or outwards?

And on the 27th of January 2023 we saw the impacts this can have. We saw what climate change induced flooding can do to a highly urbanised area. We built in areas that water needed to flow, where it needed to soak into the ground. And instead, it flooded our streets and our homes.

There is no denying that past decisions to build in certain places within Tāmaki were wrong, and that the ageing infrastructure installed is not of capacity. But when these legacy decisions were being made, the reality was that climate change was not so well understood. Despite this, it is important that we remain innovative.

Although it is frustrating to get to this point to finally see clearly what has gone wrong, we must not give up on trying to adapt. Adaptation is the word urban planners use now when they think about planning our cities for our changing climate. The foundations of our city are already built. The roads are there, the streets are there, the housing is there. But what can we change? How can we adapt?

A lot of our urban world was built using concrete. Concrete is what is called an impervious surface. Impervious means it is water repellent, water cannot soak into it. It’s like when you’re in the shower and the water hits the vinyl and runs into the drain. Whereas, if it were grass underneath your toes, it would simply soak down. It would be gross. But you get my point.

Reducing the number of impervious surfaces is super important in creating more climate resilient urban areas. Some of you may have heard the term ‘sponge city’. If you haven’t – it’s useful to think of the term quite literally. A sponge city reduces the amount of impervious surface, and creates green areas that sponge up excess water, rather than letting it run over concrete.

There are many sponge city tactics. You may have read about daylighting our streams, which involves restoring a piped stream to its natural state. This allows a path for water to flow, with opportunities to soak into the ground and provide space for vegetation to filter contaminated water. Daylighting streams is a great sponge city tactic, but it can only be performed using piped streams. Today I will tell you about a different sponge city tactic, rain gardens, which can be installed almost anywhere.

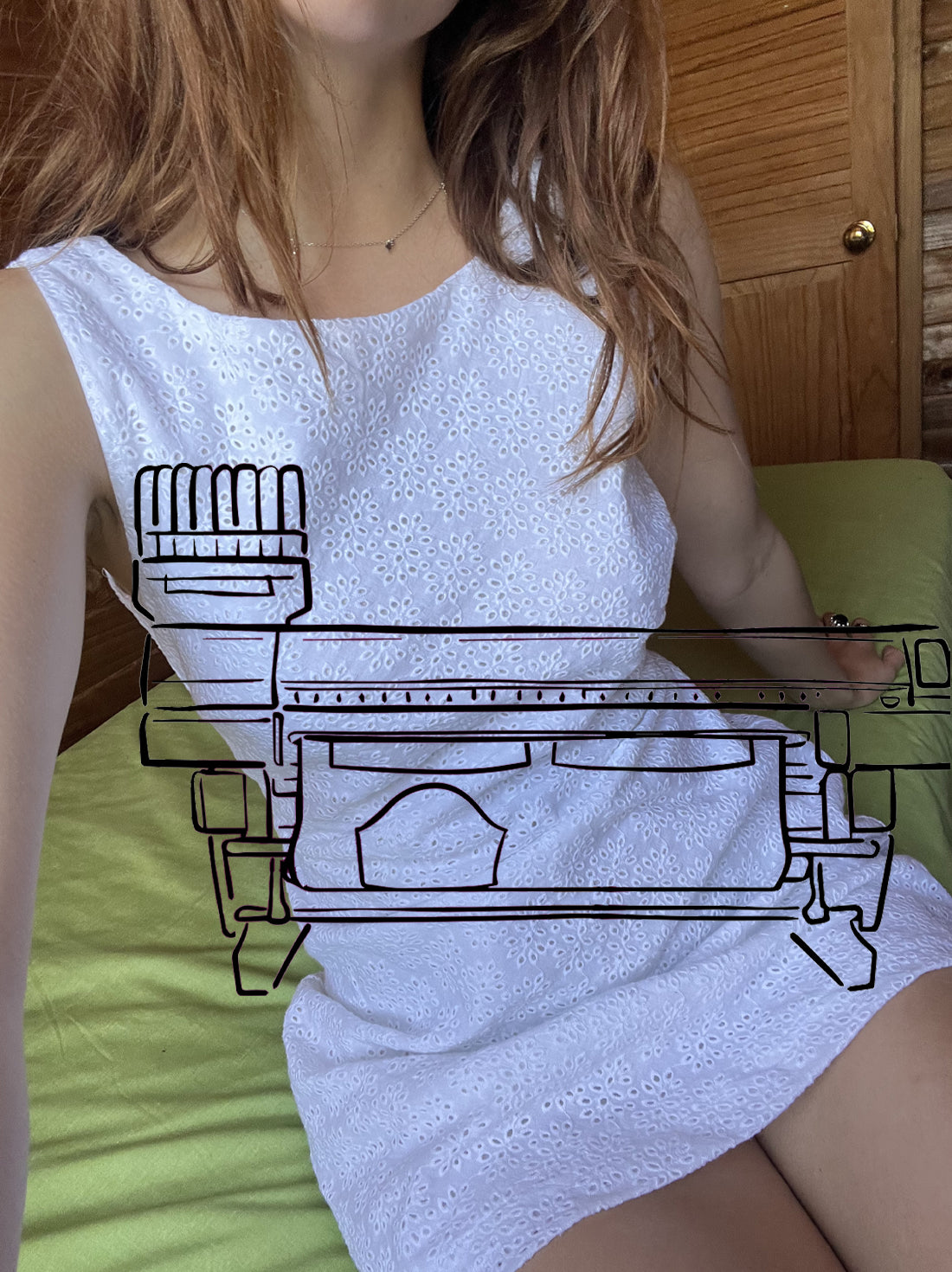

Rain Garden

In both designing new streets, and upgrading existing ones, rain gardens are a great way to ensure less imperious surface (concrete) is used. Rain gardens, pictured below, are sunken vegetation pockets along a street, between the footpath and the road. When it rains a lot, and flows start to overwhelm the network, instead of water running straight along the concrete and overwhelming below piped systems, rain gardens slow flows, by providing areas for water to soak into the ground instead. The best part is how the vegetation inside acts as a natural filter for contaminated water. Not to mention they’re pretty.

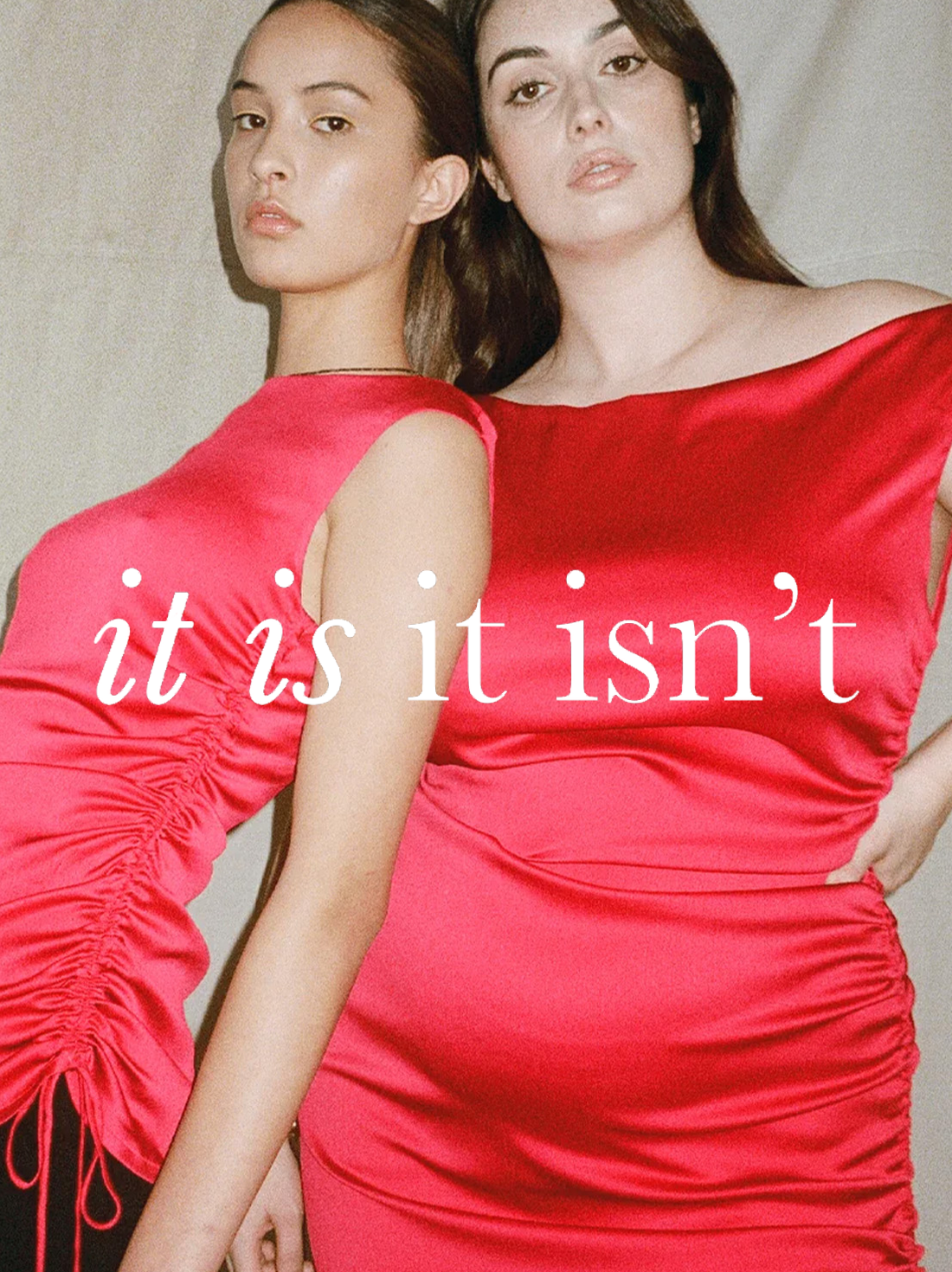

Where there is room to, rain gardens can be installed at any point in time, and on most streets. Check out the recent Quay Street upgrades near the ferry terminal in the picture above for a great example.

Next time you walk down your street, envision the possibility of rain gardens there. Think about how we have found ourselves in this tough position, as a collective we can learn how to better incorporate our natural environment into Tāmaki’s future. We can learn from our mistakes and adapt.

Written by Britt Davies

Artists impression of the Quay Street enhancements looking East.